Key Highlights

Overconfidence

Loss Aversion

Portfolio Construction and Diversification

Misuse of Information

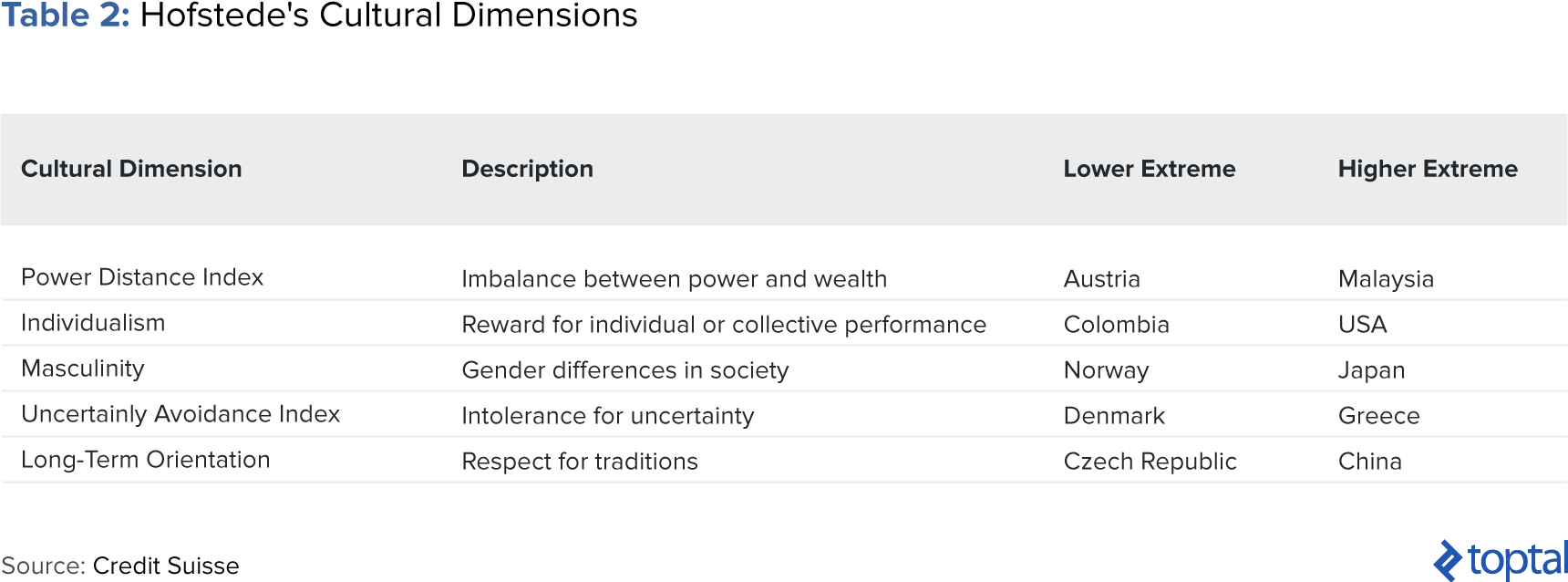

Cultural Differences in Investing

“The investor’s chief problem—and even his worst enemy—is likely to be himself.”

– Benjamin Graham

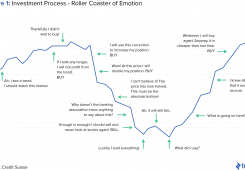

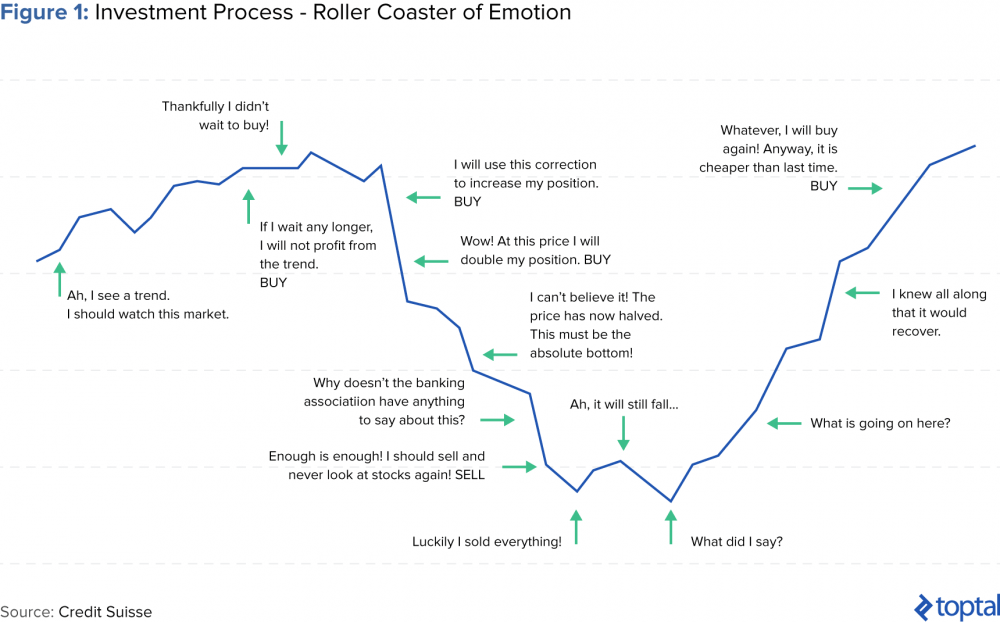

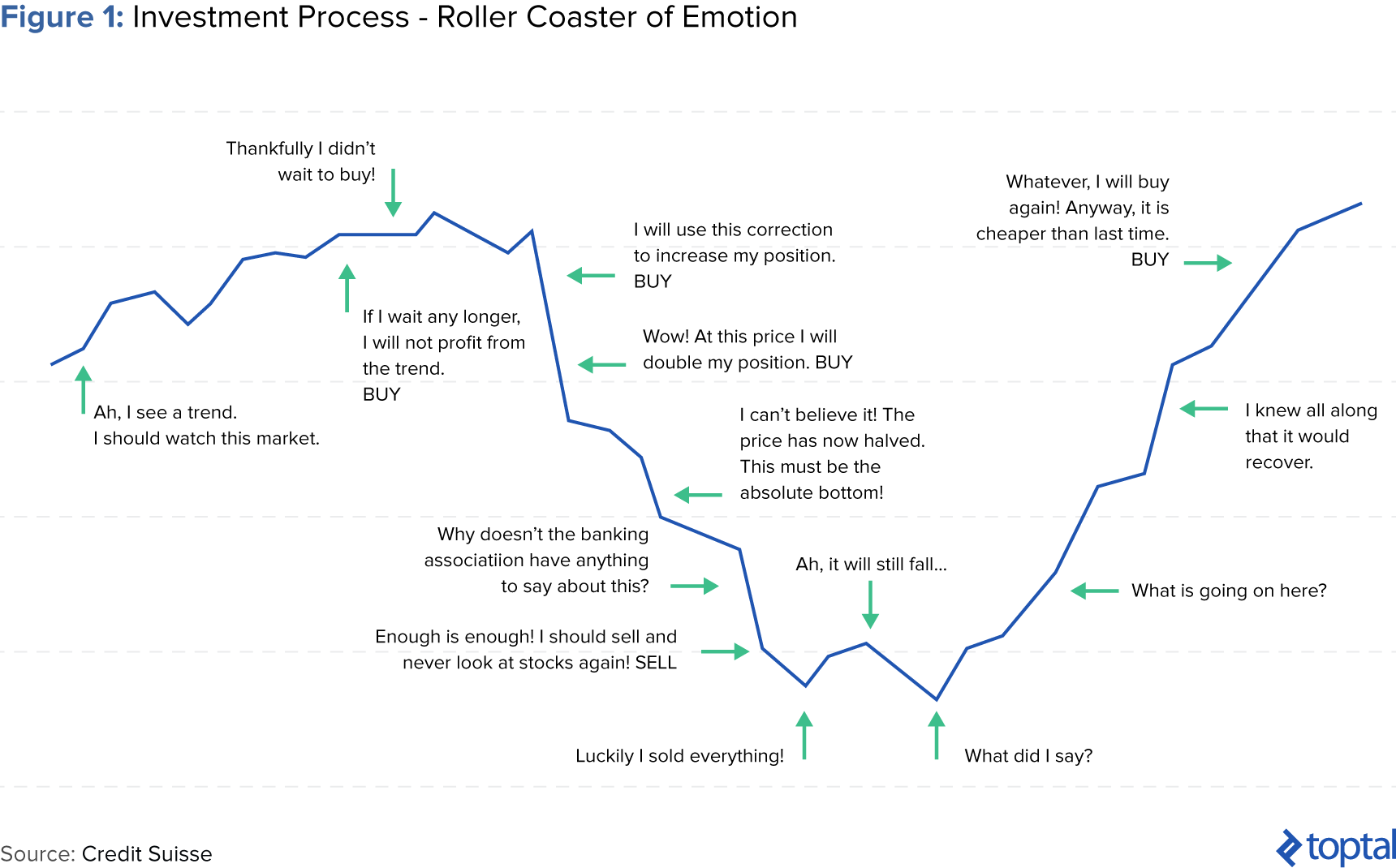

In the investment process, investors often experience the “roller coaster of emotions” illustrated below. Does this look or feel familiar to you?

If so, you’re not alone. After all, the cyclical investment process, which includes information procurement, stock picking, holding, and selling investments, followed by making a new selection, is full of psychological pitfalls. However, only by becoming aware of and actively avoiding behavioral biases can investors reach impartial decisions. The emerging field of behavioral finance aims to shed light on true financial behavior.

This piece outlines the aims of behavioral finance, the various cognitive and emotional biases investors often fall prey to, the tangible consequences these biases may lead to, and how cultural influences can affect investment decision-making.

Traditional vs. Behavioral Finance

Established economic and financial theory posits that individuals are well-informed and consistent in their decision-making. It holds that investors are “rational,” which means two things. First, that when individuals receive new information, they update their beliefs correctly. Second, individuals then make choices that are normatively acceptable. While this framework is appealingly simple, it’s clear that in reality, humans do not act rationally. In fact, humans often act irrationally–in counterproductive, systematic patterns. 80% of individual investors and 30% of institutional investors are more inertial than logical.

These deviations from theoretical predictions have paved the way for behavioral finance. Behavioral finance focuses on the cognitive and emotional aspects of investing, drawing on psychology, sociology, and even biology to investigate true financial behavior.

Behavioral Biases and Their Impact on Investment Decisions

We all have strongly-ingrained biases that exist deep within our psyche. While they can serve us well in our day-to-day lives, they can have the opposite effect with investing. Investing behavioral biases encompass both cognitive and emotional biases. While cognitive biases stem from statistical, information processing, or memory errors, an emotional bias stems from impulse or intuition and results in action based on feelings instead of facts.

Overconfidence

In general, humans tend to view the world positively. Outside of finance, in a 1980 study, 70-80% of drivers reported themselves to be in the safer half of the distribution. Multiple studies – of doctors, lawyers, students, CEOs – have also found these individuals to have unrealistically positive self-evaluations and overestimations of contributions to past positive outcomes. While confidence can be a valuable trait, it can also lead to biased investing decisions.

Overconfidence Bias

Overconfidence is an emotional bias. Overconfident investors believe they have more control over their investments than they truly do. Since investing involves complex forecasts of the future, overconfident investors may overestimate their abilities to identify successful investments. In fact, experts often overestimate their own abilities more than the average person does. In a 1998 study, affluent investors indicated that their own stock-picking skills were critical to portfolio performance. In reality, they had overlooked broader influences on performance. At its most extreme, an overconfident investor can become involved in investment fraud. Economist Steven Pressman identifies overconfidence as the primary culpritresponsible for the susceptibility of investors to financial fraud.

Self-attribution Bias

Self-attribution bias occurs when investors attribute successful outcomes to their own actions and bad outcomes to external factors. This bias is often exhibited as a means of self-protection or self-enhancement. Investors with self-attribution bias may become overconfident, which can lead to underperformance. To mitigate these effects, investors should track personal mistakes and successes and develop accountability mechanisms.

Active Trading

In many studies, it has been shown that traders who trade excessively (active traders) actually underperform the market. In a study conducted by Professors Brad Barber and Terrance Odean, investors utilizing traditional brokers (communicating via telephone) achieved better results than online traders who trade more actively and speculatively. In another of their studies Barber and Odean analyzed 78,000 U.S. household investors with accounts at the same retail brokerage house. After segmenting the group into quintiles by monthly turnover rates in their common stock portfolio, they found that active traders earned the lowest returns (see table below). They found investor overconfidence to be an important motivation for active trading.

Loss Aversion

Established financial efficient market theory holds that there is a direct relationship and trade-off between risk and return. The higher the risk associated with an investment, the greater the return. The theory assumes that investors seek the highest return for the level of risk they are willing and able to take on. Behavioral finance and related research seem to indicate otherwise.

Fear of Loss

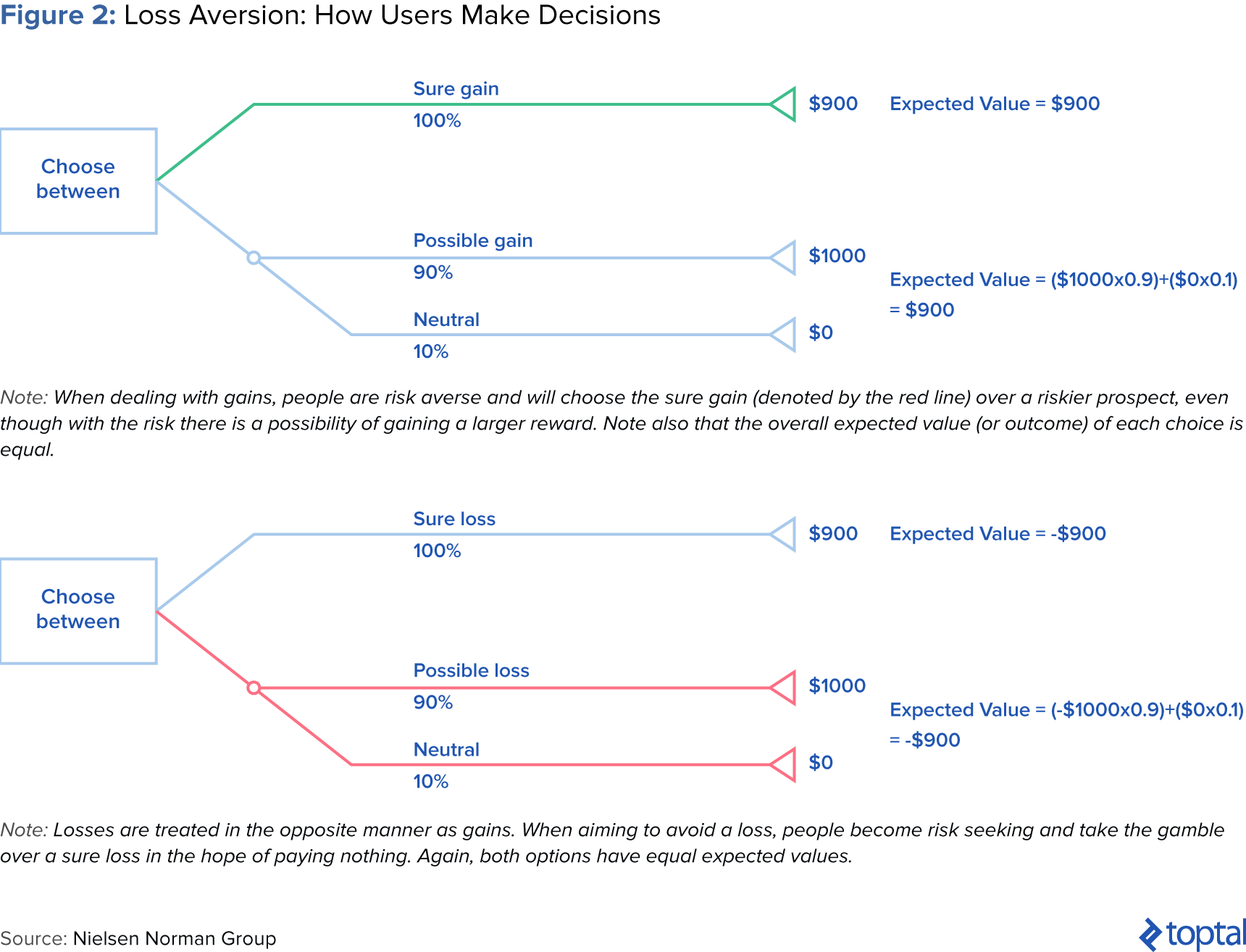

In their seminal study “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk,” behavioral finance pioneers Dan Kahneman and Amos Taversky found that investors are more sensitive to loss than to risk and possible return. In short, people prefer to avoid loss over acquiring an equivalent gain: It’s better not to lose $10 than to find $10. Some estimates suggest people weigh losses more than twice as heavily as potential gains. Even though the likelihood of a costly event may be miniscule, people would rather agree to a smaller, sure loss than risk a large expense.

For example, when asked to choose between receiving $900 or taking a 90% chance of winning $1000 (and a 10% chance of winning nothing), most people avoid the risk and take the $900. This is despite the fact that the expected outcome is the same in both cases. However, if choosing between losing $900 and take a 90% chance of losing $1000, most people would prefer the second option (with the 90% chance of losing $1000) and thus engage in the risk-seeking behavior in hopes of avoiding the loss.

Disposition Effect

As a result of their fear of loss, investors often hesitate to realize their losses and hold stocks for too long hoping for a recovery. This “disposition effect,” coined in a 1985 study by economists Hersh Shefrin and Meir Statman, is the tendency of investors to sell winning positions and hold onto losing positions. The effect can increase investors’ capital gains taxes to be paid, the regulations of which incentivize investors to defer gains as long as possible.

Berkeley business school professor Terrance Odean studied this effect, finding that in the months after the sale of “winning” investments, these investments continued to outperform the losing ones still in the portfolio. Both individual and professional investors do this across assets, including common stock options, real estate, and futures. This effect directly contradicts the famous investing rule, “Cut your losses short and let your winners run.”

For investment professionals and wealth advisors, risk of loss will remain important for clients. However, you must remind clients that “loss” is a relative term, and that you can help them find an appropriate reference point from which a gain or loss will be calculated.

Portfolio Construction and Diversification

Framing

According to the modern portfolio theory, as developed by Nobel Prize winning economist Harry Markowitz, an investment should not be evaluated alone, but rather by how it affects the portfolio as a whole. Rather than focusing on individual securities, investors should consider wealth more broadly.

In practice, however, investors tend to become hyper-focused on specific investments or investment classes. These “narrow” frames tend to increase investor sensitivity to loss. However, by evaluating investments and performance with a “wide” frame, investors exhibit a greater tendency to accept short-term losses and their effects.

Mental Accounting

The human psyche tends to bucket or categorize types of expenses or investments mentally. These buckets could include a “school fees” or “retirement,” and different accounts often hold different risk tolerances. Oftentimes, mental accounting leads people to violate traditional economic principles.

Consider this example from UChicago’s Richard Thaler: Mr. and Mrs. L went on a fishing trip in the northwest and caught some salmon. They packed the fish and sent it home on an airline, but the fish were lost in transit. They received $300 from the airline. The couple take the money, go out to dinner, and spend $225. They had never spent that much at a restaurant before.

According to Thaler, this example violates the principle of fungibility in that money is not supposed to have labels attached to it. The extravagant dinner would not have occurred had their collective salary increased by $300. Yet the couple still went because the $300 was put into both “windfall gain” and “food” accounts. Investors tend to focus less on the relationship between investments and more on individual buckets, not thinking broadly about their overall wealth positions.

Familiarity Bias

Despite obvious gains from diversification, investors prefer “familiar” investments of their own country, region, state, or company. In a study, Columbia Business School professor Gur Huberman found that in 49 out of 50 states, investors are more likely to hold shares of their local Regional Bell Operating Company (RBOC)—regional telephone companies—than of any other RBOC. Investors also prefer domestic investments over international investments. In a study conducted by professors Norman Strong and Xinzhong Xu, the professors investigated this “equity home bias.” They argue that, by itself, investors’ relative optimism about the home market cannot fully account for equity home bias.

Beyond a geographic familiarity bias, investors also exhibit strong preferences for investing in their employer’s stock. This can be dangerous for employees because, if employees devote a large portion of their portfolios to their own company’s shares, they risk compounding losses if the company performs poorly: first, in loss of compensation and job security, and second, in loss of retirement savings.

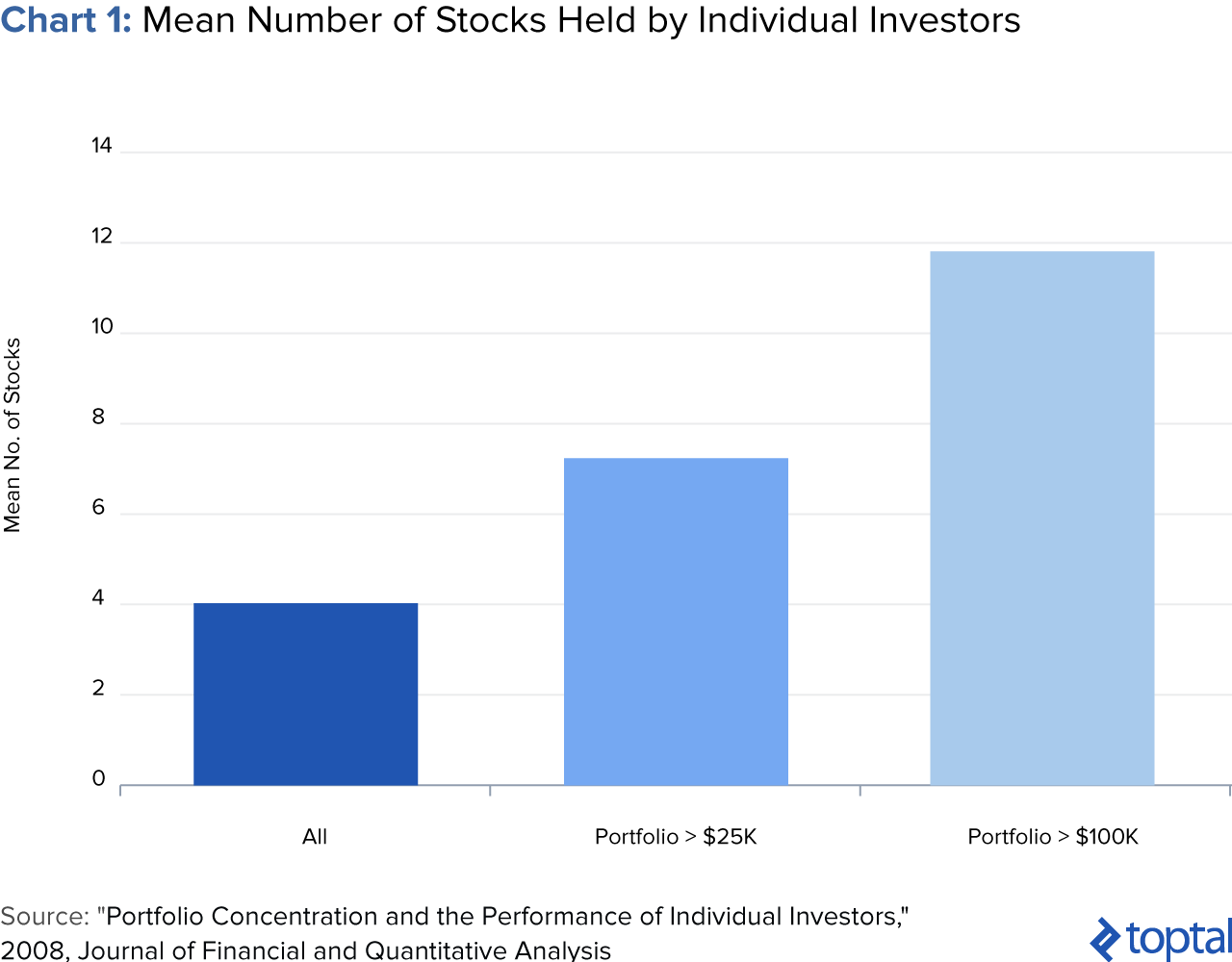

An implication of familiarity bias is that investors hold suboptimal portfolios and suffer from under-diversification. Although the best practice is for portfolios to hold at least 300 stocks, the average investor only holds three or four. The average investor’s concentration in employer, large-capitalization, and domestic stocks work against the advantages of diversification. To overcome this bias, investors need to cast a wider net.