Pricing is one of the most important financial levers that companies have at their disposal to influence the financial success of their business. However, it is not an easy task.

Firstly, pricing affects multiple stakeholders, both inside and outside the company. Experimenting with pricing is therefore not a task that should be taken lightly. Secondly, finding the right price is notoriously hard. Customer preferences are hard to gauge ex-ante, and internally, it can be difficult to foresee the effects of pricing changes on the financial performance of a company. And finally, of course, pricing doesn’t happen in a vacuum. In any competitive market, pricing changes can often lead to retaliatory actions which end up canceling out the intended effect of the pricing adjustment.

With this in mind, techniques and methods for getting around these challenges are extremely useful.

In my experience, having co-founded a developer tools startup that uses a SaaS model, I have come to appreciate the SaaS business model as being, amongst other things, very pricing-friendly. The intrinsic characteristics of SaaS and its delivery mechanism have important ramifications related to pricing which, in turn, can be extremely useful in the financial management of your company.

In this article, I explore in more detail what these are and how they can benefit your business from a financial analysis and management standpoint.

What is SaaS?

Software as a Service (SaaS) is a software licensing and delivery model in which software is licensed by a third party and delivered to clients through the internet. Compared to locally hosted software models, SaaS clients do not have to install the software, update it, maintain it and integrate it. The vast majority of technical aspects are “taken care of” by the SaaS provider so that the client can start using the SaaS product with little effort.

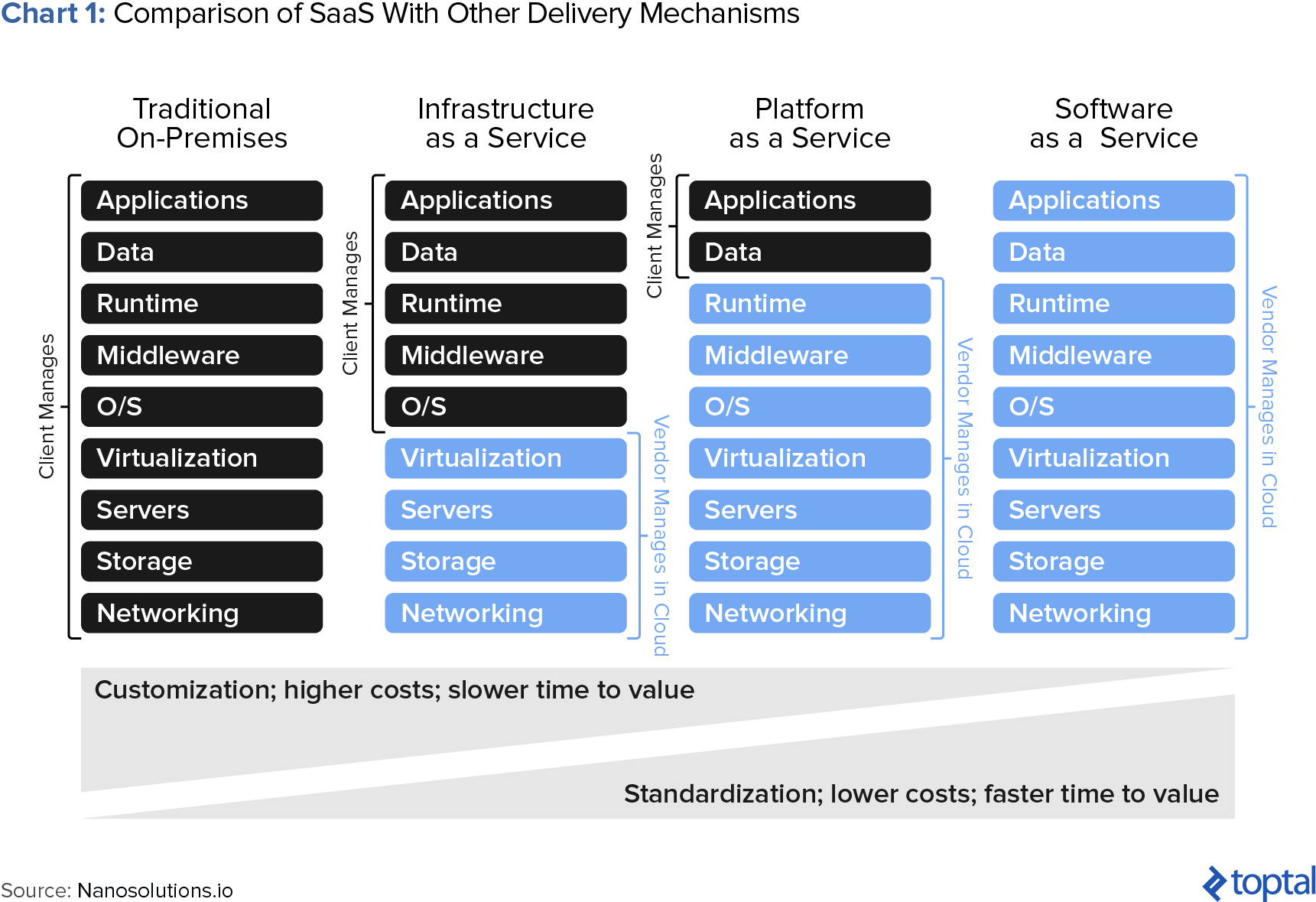

The ramifications and benefits of SaaS versus other types of services are displayed graphically in chart 1 below. As you can see, with traditional on-premises software, the client has to manage most of the activities related to setting up and running the software. At the opposite end of the spectrum, SaaS takes care of all of this on the software provider’s side. There are shades in between; for instance, Infrastructure as a Service and Platform as a Service.

The pros and cons of SaaS are fairly straightforward. On the one hand, SaaS is much easier to set up and run. It doesn’t require local servers, storage, management, etc. On the other hand, it doesn’t allow the same level of customizability that on-premises software can provide.

The change from locally hosted software to SaaS has been happening for some time, and is part of a more general shift in the IT industry to cloud-based applications. According to FTI Consulting, 69% of businesses today use at least one cloud-based application.

The shift to SaaS from on-premise services can be seen nicely when one looks at Adobe, one of the industry’s most well-known players. As can be seen in chart 2, courtesy of Tom Tunguz, Adobe’s non-SaaS product revenue peaked in 2011 at $3.4 billion and halved to $1.6 billion in just three years. Such a drop in revenue would normally have huge ramifications, but Adobe has also been offering a suite of SaaS products, which have increased in revenue five-fold, from $0.45 billion in 2011 to $2.1 billion in 2014. Adobe’s changing product mix is indicative of the overall industry’s shift away from locally hosted software towards cloud-based software provision, such as SaaS.

All indications are that this trend is likely to continue. Gartner estimates that SaaS application software was a $144 billion market in 2016 and that, by 2020, businesses will be shifting to cloud-based software to the tune of $216 billion a year.

SaaS Is a Pricing-friendly Business Model

As mentioned, the reasons for this shift to cloud-based applications are manifold. Lower setup and maintenance costs are of course a big factor. However, one important benefit that I have found of SaaS-based applications is that they are very pricing friendly. This is win-win both for clients as well as for the businesses providing the service, and I believe it plays an important role in explaining the overall industry shift.

In particular, there are several intrinsic operational characteristics of SaaS as a business model that in turn have implications on pricing, and specifically create and magnify the number of pricing levers that businesses have at their disposal. In particular, I highlight four main pricing-related benefits of SaaS products:

- Flexibility: Because of the web-based, real-time nature of the delivery mechanism, SaaS products are very flexible and allow for constant iteration. This affects pricing as well, since changes to pricing can be relatively quickly implemented, and the impact of these changes can be immediately measured. One can keep iterating until the desired price is reached.

- Real-Time Usage Tracking: Since SaaS products are in the cloud, usage of the software by the client is tracked in real time on the service providers’ side. This means that SaaS companies are more able to charge on a per-usage basis than traditional on-premises companies. This in turn has several important benefits detailed below.

- Network effects: The delivery mechanism and frictionless implementation of SaaS products acts as an enabler of network effects. This has important pricing ramifications in that it makes it easier to both create and charge for these network effects, thus in theory maximizing monetization.

- Freemium: Due to near zero marginal costs of delivery and product hosting, SaaS companies are more able to allow clients to use certain products for free for months or even years until they upgrade or cancel the service. Freemium prevents the product pricing from being a barrier to users trying or adopting the product, thus increasing the number of potential clients.

Benefit No. 1: Pricing Flexibility

The first and arguably most important financial benefit of adopting a SaaS model is the inherent flexibility that the model provides. In particular, flexibility refers to the following attributes:

- Fast iteration: Because of the delivery mechanism, SaaS allows you to iterate quickly on pricing changes so that you can test price points and packages until you reach the optimum mix.

- Tiered pricing: SaaS lends itself very well to tiered pricing, meaning the ability to price different product offerings differently to address multiple customer sub-segments.

- No middleman: Since SaaS is delivered right to the client, bypassing any middlemen. This removes a key stakeholder from the equation and again gives the company greater flexibility to test different pricing points and packages

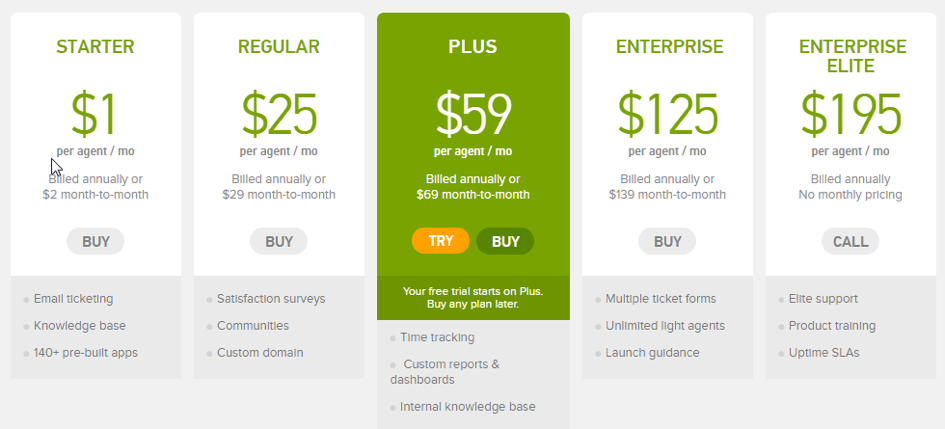

A practical example of this can be observed by analyzing Zendesk’s pricing evolution. Zendesk is a very successful customer service software company that generates over $300 million in yearly revenue. It offers different features of the same product to different customer segments.

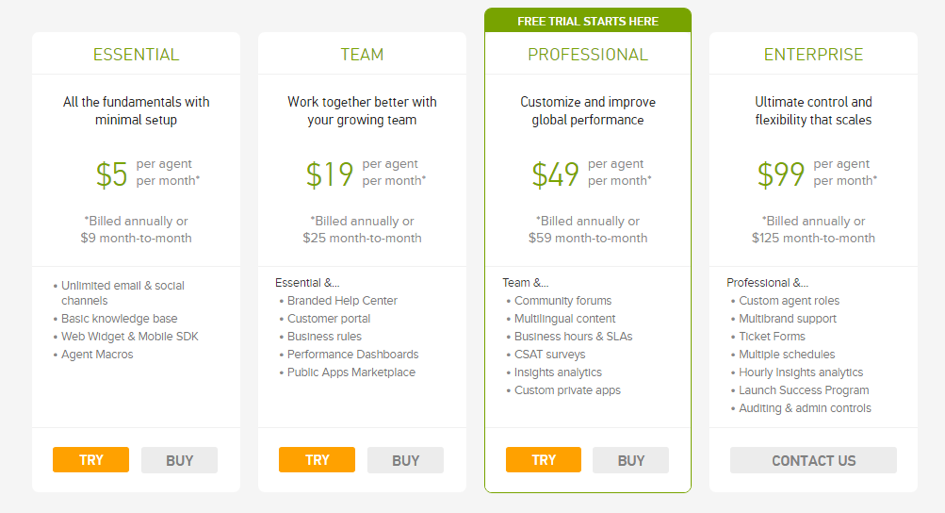

As seen in the example below, in January 2015, Zendesk offered five different plans for five different segments. Its cheapest plan was available at $1 per agent per month while its most expensive was at $195 per agent per month. It also directed the users towards the “Plus” plan by highlighting it in green.

Exhibit 2: Zendesk January 2015 Pricing Options

Source: Archive.org

In January, 2016, Zendesk must have felt that there was room for improvement in pricing; they decreased the total number of plans from five to four. They also made changes in the pricing of plans where the least expensive plan increased from $1 to $5 per agent per month while its most expensive plan decreased from $199 to $99 per agent per month. The names of the plans were also changed (e.g., “Starter” to “Essential”) and the users were directed to the “Professional” plan by a lighter highlighting technique.

Exhibit 3: Zendesk January 2016 Pricing Options

Source: Archive.org

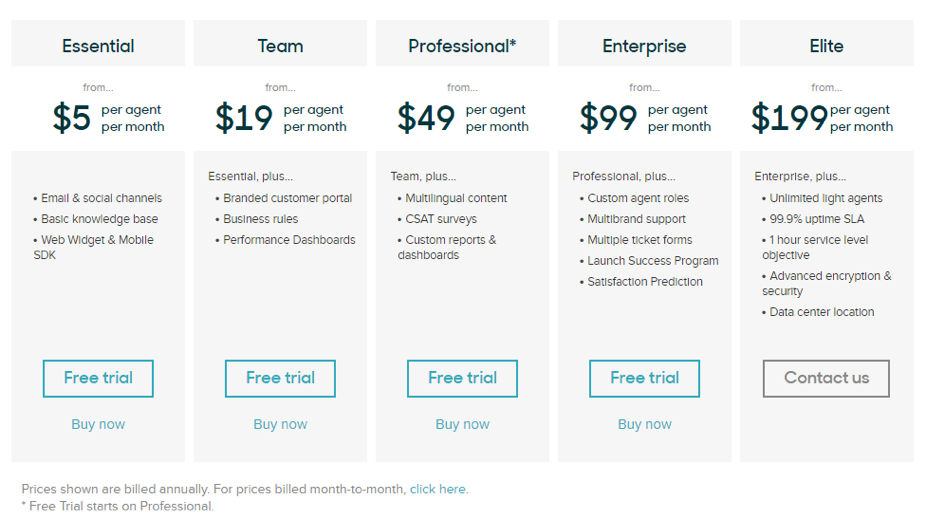

In 2017, pricing changed again and the number of plans increased back to five. While the least expensive plan stayed at $5 per agent per month, its most expensive plan increased from $99 to $199 per agent per month. By removing highlights, Zendesk stopped directing people to any of the plans.

Exhibit 4: Zendesk January 2017 Pricing Options

Source: Zendesk Pricing Page

Zendesk unfortunately doesn’t disclose the specific effects that its pricing changes have had. Nevertheless, the more general point that flexibility is useful is summarized nicely in this post: “Finding the right balance between value and revenue – your ability to help customers and be fairly compensated for that help – will make or break your […] company.” No doubt Zendesk’s changes are a reflection of this point.

To sum up, SaaS, as a delivery mechanism, allows for a great deal of flexibility and iterating capacity when it comes to pricing. As Lincoln Murphy of Sixteen Ventures puts it, “Pricing (like pretty much everything) is never a set-it-and-forget-it situation,” so the ability to iterate, test, learn, and improve is a very useful feature of the SaaS business model.

Cohort Analysis

If the results of pricing changes cannot be measured in a definite way, there is no point in iterating. So it is important to set up appropriate data collection and measurement processes and tools from the start.

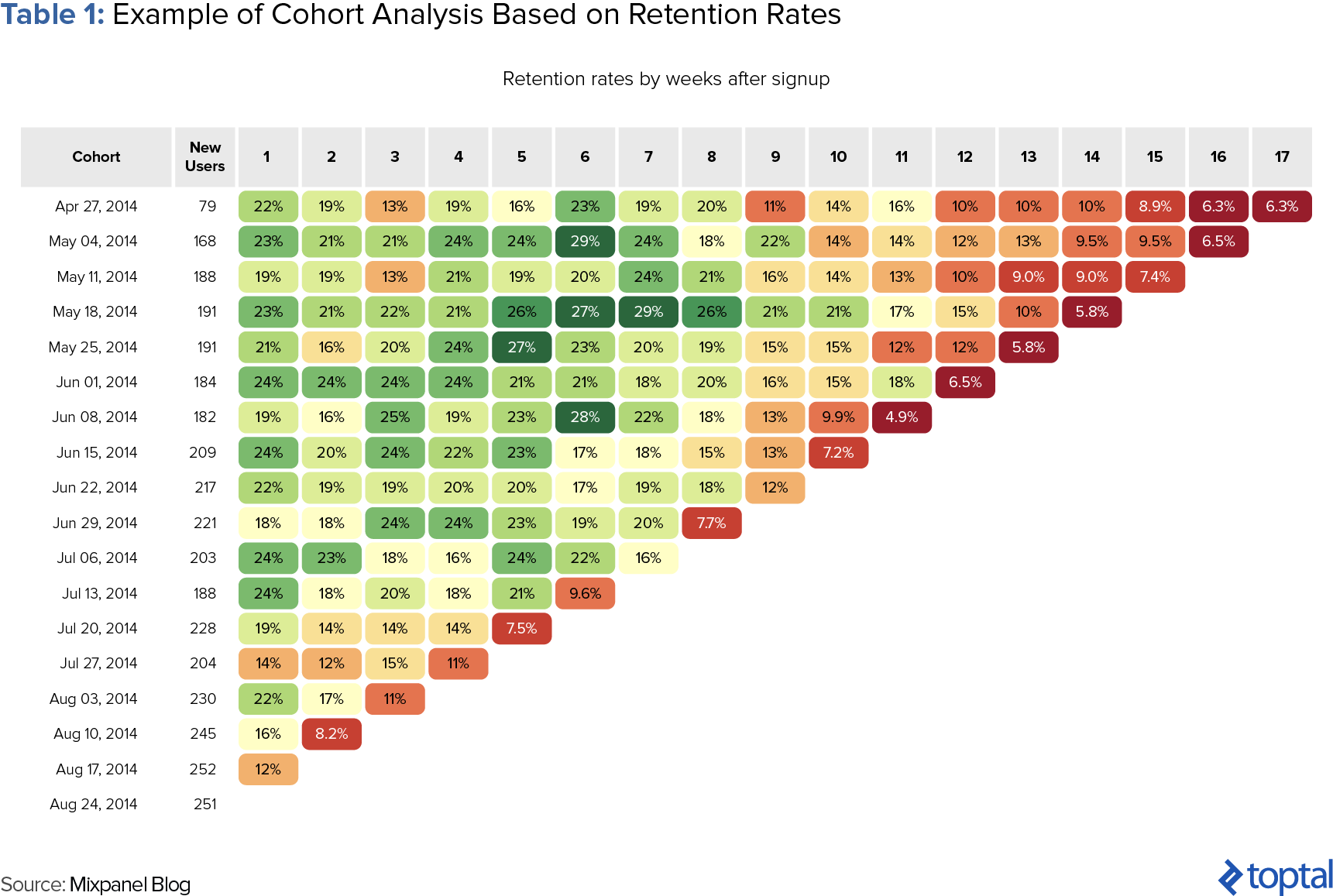

One of the ways of measuring the results is through a cohort analysis. In cohort analysis, customers are put in different cohorts (i.e., groups) based on a characteristic, typically a selected time period. All of the new customers signing up can be divided into cohorts based on the date they become a customer. For example, there could be different cohorts as customers who joined in January, February, March, etc.

Analytics tools like Mixpanel readily offer cohort analysis based on the data they gather. As seen in the example above (Table 1), retention is being analyzed to measure how many people keep using a fictitious product as time passes. Going into the details, the cohort of April 27, 2014 has a retention rate of 23% at week 6, meaning that 23% of people who signed up in the week of April 27 2014 are still using the product at week 6. The cohort of July 13, 2014 has a retention rate of 9.6% in week 6, indicating a significant drop in retention rates, which means a major problem with this cohort or an action taken within that timeframe.

The critical aspect of cohort analysis is availability of data, so it is crucial that the data that will be the basis of the cohort analysis is collected correctly and available when needed.

Less Is More

In a well-known study conducted by psychologists Sheena Iyengar and Mark Lepper, it was showed that excessive choice can produce “choice paralysis.” As explained in this HBR article:

“[…] shoppers at an upscale food market saw a display table with 24 varieties of gourmet jam. Those who sampled the spreads received a coupon for $1 off any jam. On another day, shoppers saw a similar table, except that only six varieties of the jam were on display. The large display attracted more interest than the small one. But when the time came to purchase, people who saw the large display were one-tenth as likely to buy as people who saw the small display.”

Due to tiered pricing, the absence of intermediaries, and the fast iteration capabilities of SaaS, a product could be offered in hundreds of different ways. Nevertheless, one has to be careful not to create an instance of choice paralysis; thus, it is paramount that pricing be approached from a design perspective as well.

A practical example of this can be observed with Hubspot. Hubspot is an inbound marketing and sales management platform that automatizes and makes email marketing, analytics, and SEO more effective. PriceIntellingently does a nice job of explaining how although Hubspot’s pricing could be displayed in a variety of ways (e.g., a moving bar that shows the increase in pricing as the number of contacts increase), only three different plans were created based on three different value metrics. This makes these plans easier to understand and track.

Benefit No. 2: “Per-usage” Pricing

The second key benefit of SaaS products is that because of the delivery mechanism, SaaS lends itself much better to per-usage pricing. This is because usage by the client can be tracked and measured appropriately since the software is run on the service provider’s side.

Per-usage pricing is a very useful pricing tool for the following reasons:

It creates a lower barrier to customer adoption.

Users face a lower up-front financial barrier to signing up for the service since they know that their expenses will be in line with their usage. In contrast, traditional on-premises software usually charges a flat up-front fee based on an estimated assumption of usage. This estimate may not necessarily correlate with the specific needs of the client in question.

As outlined by Reason Street in this article, “Because of low or no cost startup fees, enterprise customers that typically take six months to a year to make a decision about enterprise software often leap frog this decision and simply begin to try the service. Customers then increase their use based on actual need of the company (vs. paying up front for licensing fees per seat).”

Costs can be better aligned with revenues.

Per-usage pricing also allows the service provider to better align its own costs with its revenues, since the revenue it receives is tied to the costs it incurs to charge the service. As Reason Street again points out, “For software startups, particularly in the SaaS sector, once the initial minimum viable product is built, companies can scale revenue closer to the scale in costs required to deliver the service. Some SaaS companies prefer pay-per-use, because the value relationship is made very clear to the customer, and they are able to prioritize feature and service development based on the customer’s expressed needs.”

Per-usage pricing leads to greater stickiness.

Per-usage pricing often leads to greater customer stickiness for two important reasons.

Firstly, since the customer’s expenses are spread out over a great period of time, their costs at any given point in time will be small compared to other costs that their businesses incur. As a result, they may not be as tempted to cut these. Of course, if the client were to view the costs as a whole (or over a longer period of time) they may well notice that the total cost is much larger, but human psychology doesn’t always follow logic.

Secondly, since per-usage pricing leads to lower barriers to adoption (as explained above), customers are more likely to give the service a try. As they continue using the service, the software may become more embedded in the everyday processes of the company, making it more difficult and costly to switch providers. Andreessen Horowitz sums this point and the related benefits up nicely:

“Once a SaaS company has generated enough cash from its installed customer base to cover the cost of acquiring new customers, those customers stay for a long time. These businesses are inherently sticky because the customer has essentially outsourced running its software to the vendor […]

It’s very difficult to switch SaaS vendors once they’re embedded into business workflow. SaaS customers, by definition, made the decision to have an outside vendor manage the application. In the perpetual license model, in-house IT staff managed all software instances and thus could incur the internal costs to switch vendors if they so chose.”

Per-usage pricing allows for subscription pricing, which helps with financial planning.

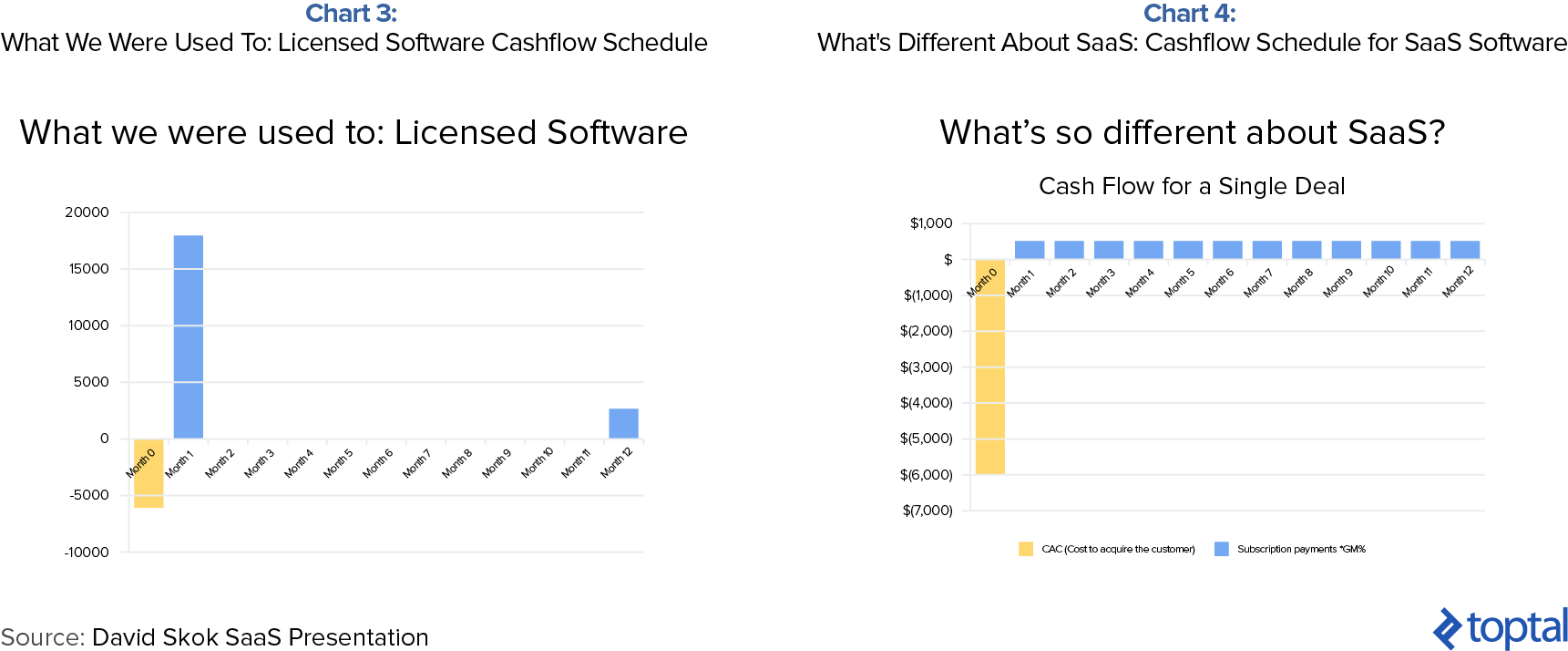

To be clear, per-usage pricing is not necessarily always good. There is a clear cash flow tradeoff from switching from up-front licensing to per-usage pricing. This effect is again illustrated nicely by Andreessen Horowitz:

“In the traditional software world, companies like Oracle and SAP do most of their business by selling a ‘perpetual’ license to their software and then later selling upgrades. In this model, customers pay for the software license up front and then typically pay a recurring annual maintenance fee (about 15-20% of the original license fee). Those of us who came from this world would call this transaction a “cashectomy”: The customer asks how much the software costs and the salesperson then asks the customer how much budget they have; miraculously, the cost equals the budget and, voilà, the cashectomy operation is complete.

This is great for old-line software companies and it’s great for traditional income statement accounting. Why? Because the timing of revenue and expenses are perfectly aligned. All of the license fee costs go directly to the revenue line and all of the associated costs get reflected as well, so a $1M license fee sold in the quarter shows up as $1M in revenue in the quarter. That’s how traditional software companies can get to profitability on the income statement early on in their lifecycles.

Now compare that to what happens with SaaS. Instead of purchasing a perpetual license to the software, the customer is signing up to use the software on an ongoing basis, via a service-based model — hence the term “software as a service”. Even though a customer typically signs a contract for 12-24 months, the company does not get to recognize those 12-24 months of fees as revenue up front. Rather, the accounting rules require that the company recognize revenue as the software service is delivered (so for a 12-month contract, revenue is recognized each month at 1/12 of the total contract value).

Yet the company incurred almost all its costs to be able to acquire that customer in the first place — sales and marketing, developing and maintaining the software, hosting infrastructure — up front. Many of these up-front expenses don’t get recognized over time in the income statement and therein lies the rub: The timing of revenue and expenses are misaligned.”

This effect is displayed graphically in Charts 3 and 4 below:

Nevertheless, as can be seen clearly from the chart above, the major benefit of subscription pricing is that it provides a much steadier, more predictable cash flow cycle, which in turn can be of great help when it comes to financial planning. This helps to explains why the vast majority of SaaS products are priced on a subscription/monthly basis.

Benefit No. 3: Create and Charge for Network Effects

Another important pricing benefit of SaaS products is that, since these lend themselves well to network effects, this has useful implications for pricing. To be clear, when we say that SaaS “lends itself well to network effects,” what we mean is that a) SaaS can be an enabler for creating network effects, and b) SaaS as a delivery mechanism is often more practical for activities that benefit from natural network effects already. Before moving on to looking at the pricing implications of this point, we delve a little deeper into how SaaS lends itself well to network effects.

SaaS as a Powerful Enabler of Network Effects

As mentioned, the specific attributes of SaaS products often mean that these can be powerful enablers for network effects. Specifically, there are three reasons:

1) SaaS makes for good collaboration software, since it is delivered over the internet.

By using the internet, rather than locally hosted delivery, SaaS software allows people to collaborate in real time (e.g., Google Docs) and view things simultaneously. It also avoids interoperability issues between different users (perhaps due to their operating systems), again making for easier collaboration.

As pointed out here, the ease of collaboration for SaaS products is “why collaboration is one of the most heavily populated and fastest-changing SaaS categories.” Examples of companies in this space include services like Campfire for team collaboration, Basecamp for project management, AnyMeeting for web conferencing, Vidyo for video conferencing, Box for storage, and Google Apps for productivity.

2) SaaS makes it easier to work with external sources, since there are fewer interoperability issues.

Most businesses have to interact with multiple third parties, be it vendors, suppliers, freelancers, etc. When software is used to work together, interoperability of this software becomes an issue. SaaS solves this by removing interoperability (aside from interoperability at the browser level, which is fairly minimal in most cases). As outlined here, “there is the obvious one which is actually connecting businesses to each other. For instance, if your are in purchasing management and you connect companies to possible suppliers, such as Kinnek does. This creates market place like network effects where more suppliers create more value buyers and vice versa.”

A corollary to this is that, since SaaS is relatively easy to set up and get running, it adds less friction when convincing other parties to run the same software as you, which again makes it easier to create network effects.

3) SaaS allows for data-enabled network effects.

Since SaaS allows for real-time data tracking, it can also lead to so-called data-enabled network effects. In this fascinating blog post by Tomas Tunguz, Venture Capitalist at Redpoint Ventures, he outlines this point (specifically referring to SaaS Enabled Marketplaces) as follows:

“Because SEMs deploy SaaS to both the supply side and the demand side, these companies can develop an exceptional understanding of their market. Access to supplier data and consumer demand provides four key advantages to SEMs.

First, SEMs understand the supply/demand curve at every second […] Consequently, if there is a supply/demand imbalance, the SEM can [step in to] balance the market place.

Second, SEMs understand the operational excellence of their suppliers […] The SEM can better qualify and match supply and demand.

Third, the accumulated data on both consumer demand and supplier performance compounds into a unique data asset that erects a moat around the business.

Fourth, because of the visibility into supply/demand, a deep understanding of supplier excellence, and the ability to identify the right types of buyers and sellers, SEMs benefit from a more efficient go to market.”

The Pricing Benefits of Network Effects

The pricing benefit of the above is that SaaS makes it easier to price products so that network effects are at first encouraged, and later taken advantage of. Specifically, because of the delivery mechanism, SaaS makes it easier to implement pay-per-account or pay-per-user pricing systems.

The benefits of per-user pricing with relation to network effects can be summarized as follows: Since on a per-user basis the cost is relatively low, this introduces little friction for companies to try out a service. If they do so, and assuming they like it, this in turn kicks into gear the creation of network effects. Once the network effects take hold, the companies roll out the SaaS product to the wider organization, which in turn allows the per-user pricing model to “ride” the rollout and capture maximum revenue. In many cases, no discount for large volume is offered because of the “addiction” to the service that the network effect has created.

A good example of the above is JIRA. JIRA is project management and issue tracking software product provided by Atlassian, a $6 billion Australian SaaS products company. JIRA allows developers to document and review bugs and other issues, as well as to perform project management functions. The more people who use JIRA, the more valuable JIRA is to each user.

As a result of this, JIRA’s pricing reflects the network effects. As the number of users using the product increases, the per-user pricing actually increases. For a small team of ten people, per user pricing is $10 while at fifty people, per-user pricing increases to $50, which is a fivefold increase (Table 2).

While the exact effect of this pricing is impossible to know, a quick look at Atlassian’s annual report (page 44 and 49) shows that subscriber revenue increased by 1200% ($12.24 million in 2014 to $146.66 million in 2016) while its customer numbers increased 80% (37,250 in 2014 to 60,950 in 2016). A simple math shows that if pricing stayed same, Atlassian’s revenues would be only $22 million due to an 80% increase in number of customers. In other words, thanks to changes in its pricing, Atlassian generates an additional $124 million ($146 million – $22 million) per year!

The overall point of charging for network effects is summarized nicely in this academic paper: “The presence of network effect also favors pay-per-use over perpetual licensing; if the network effect is strong, pay-per-use will always dominate perpetual licensing regardless of the inconvenience cost or the potential piracy. With more heterogeneous consumers, higher potential piracy, lower inconvenience costs, and stronger network effects, pay-per-use licensing yields not only higher vendor profits but also a higher social surplus than perpetual licensing.”

Benefit No. 4: Freemium – Pricing as a Marketing Strategy

Freemium is a marketing strategy where a part or all of the product is offered with zero pricing for unlimited time. The “-mium” portion of the word “freemium” refers to “premium,” where the user of the free product could upgrade to a premium product, i.e., pay for the product. Freemium is offered in the hope that some of the users of the free product would upgrade to premium, but this offer is for unlimited time, so the users can upgrade whenever they please.

The benefits of freemium are summarized nicely in this Harvard Business Review article:

“Several factors contribute to the appeal of a freemium strategy. Because free features are a potent marketing tool, the model allows a new venture to scale up and attract a user base without expending resources on costly ad campaigns or a traditional sales force. The monthly subscription fees typically charged are proving to be a more sustainable source of revenue than the advertising model prevalent among online firms in the early 2000s. Social networks are powerful drivers: Many services offer incentives for referring friends (which is more appealing when the product is free). And freemium is more successful than 30-day free trials or other limited-term offers, because customers have become wary of cumbersome cancellation processes and find indefinite free access more compelling.”

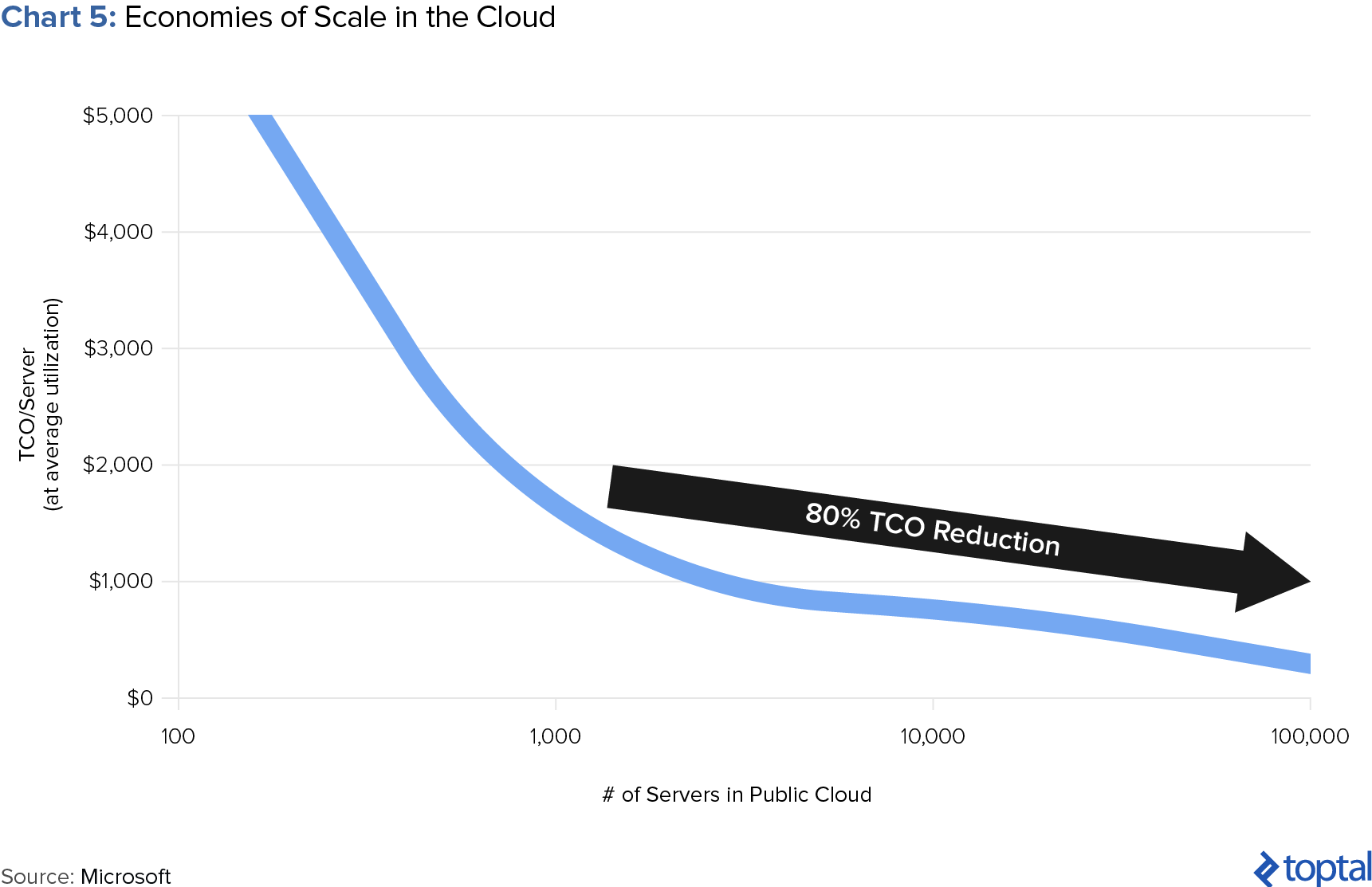

The pertinence of this to the SaaS model is that freemium only works if the cost of delivering the service for free is marginal. If not, freemium is unlikely to work from a financial standpoint. Fortunately for SaaS, this is one of the inherent benefits of the delivery mechanism (Chart 5).

As such, SaaS lends itself very well to offering freemium pricing. This point is summarized nicely in this post,

“For the freemium model to work out, one specific product attribute must already be in place – low marginal distribution and production cost. Only if you can keep the cost as low as possible, an additional free user will cost you nothing more than a database entry […] this is an inherent characteristic of SaaS products”

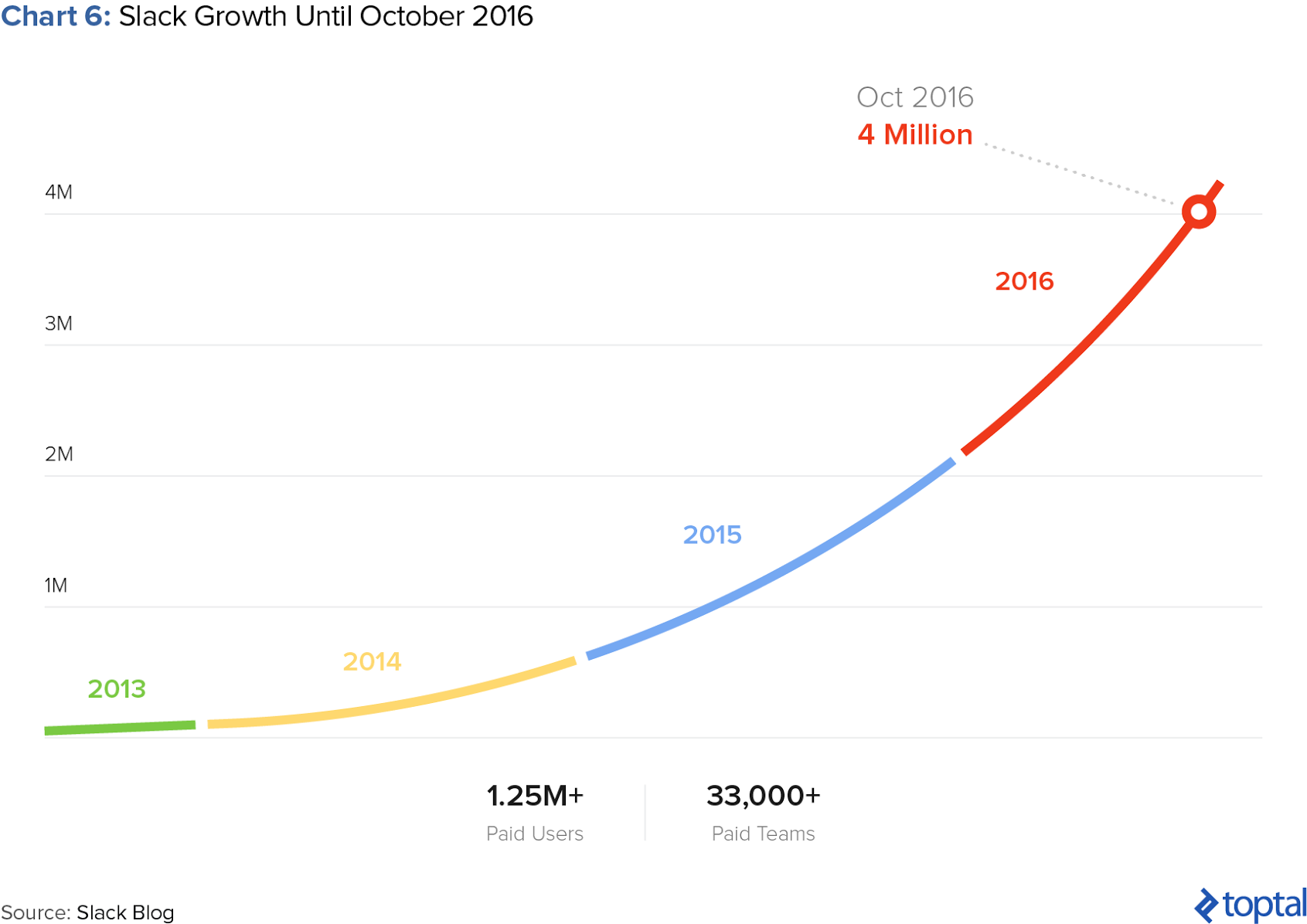

A company that has a great freemium SaaS offering is Slack, which has over 4 million daily active users at the moment. Out of these users, 1.25 million are paid but the remaining 2.75 million are using the product for free. Pricing does not prevent them from using the product and makes them potential paid users in the months and years to come. In other words, many leads are acquired thanks to zero-dollar pricing.

Slack seems to be benefiting from its freemium structure, with a 30% claimed conversion rate. In other words, of the 2.75 million users who are using Slack for free, 800,000 are expected to become paid users in the future. That is lots of additional recurring revenue; to be somewhat precise, at $6.67/month/user with its cheapest paid plan, that is an additional of $5.3 million in revenue per month.

Not all products are created equally; thus, each product could have a different freemium offering and conversion rate. For example, while Spotify has a 27% freemium to premium conversion rate, Dropbox has a rate of 4%. Therefore, each company should figure out whether freemium is doable. Nevertheless, as Ben Chestnut, co-founder of MailChimp, puts it, Ben & Jerry’s free ice cream day showed that freemium could be quite powerful and has been for MailChimp since they started offering it, eight long years after they founded the company.

N.B. In this article, Freemium is defined as offering a product to a customer for unlimited time. A free trial is defined as offering a paid product to a customer for a given time. A free trial is not considered freemium, as it cannot be offered indefinitely. To further read the implementation of freemium and free trials, please check out this article from Lincoln Murphy.

On Cloud Nine

As more and more companies switch to cloud-based provision of services, the shift to SaaS from On-Premises software is likely to continue at a steady pace. And we think this is a good thing. Startups will find it easier to offer the same services that larger, more established companies have only been able to do thanks to large investments in in-house capabilities. Consumers will have greater flexibility to find products that balance their needs with their wallets. In other words, SaaS creates win-wins across the spectrum.

As SaaS technology and our understanding of its benefits develop, we expect to see more pricing models emerge to take advantage of this unique model. The examples above are not exhaustive, and are just a reflection of the types of pricing implementations used in the SaaS world, but I hope this article may serve as a guide for continuous pricing challenges and opportunities.